E1: How it all started- From atoms to planets

Have you ever looked at the night sky and wondered about the origins of everything? Not just the twinkling stars, but the very ground beneath our feet, the air we breathe (though plants don’t actually create the oxygen!), water, the silicon in the device you are reading this on, and everything else out there?

The origin of elements

The Big Bang (Oh, it was silent by the way)

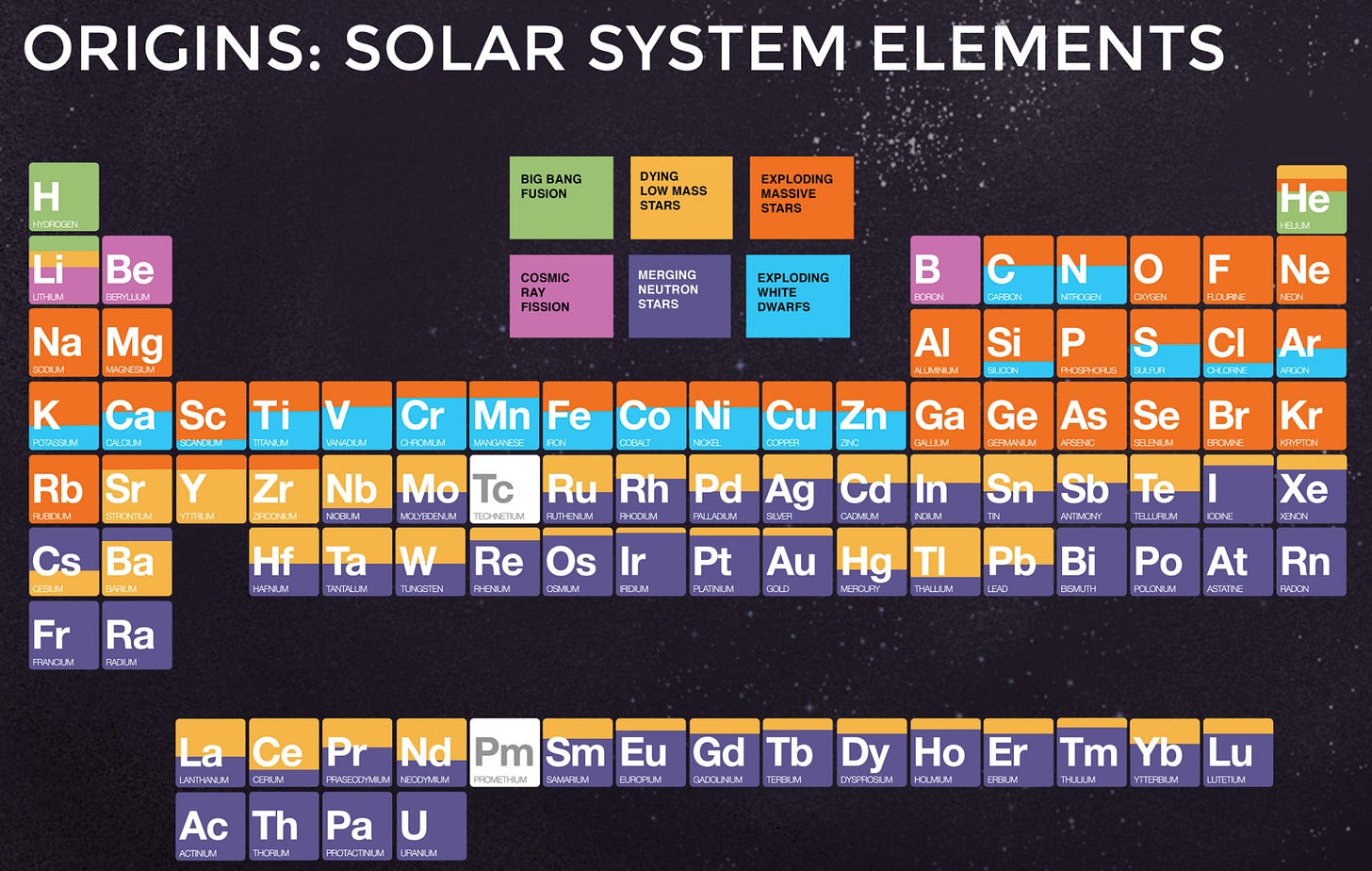

About 13.8 billion years ago, the Big Bang emitted gigantic amounts of subatomic matter, which then formed protons, neutrons and electrons that are the building blocks of all elements. As the universe expanded and cooled from its incredibly hot and dense state, conditions were perfect for the first, simplest elements to form: Hydrogen (H), the most common, Helium (He), the second simplest, and a tiny bit (on a cosmic scale) of Lithium (Li).

Nearly 200 million years later, vast clouds of Hydrogen and Helium got close to each other due to gravity until it got hot and dense enough to initiate nuclear fusion, creating the first stars. The stars that succeed in achieving nuclear fusion of Hydrogen enter their main sequence: proton-proton (p-p) chain, where Hydrogen fuses to make Helium. This process of creating new elements by fusion is called nucleosynthesis.

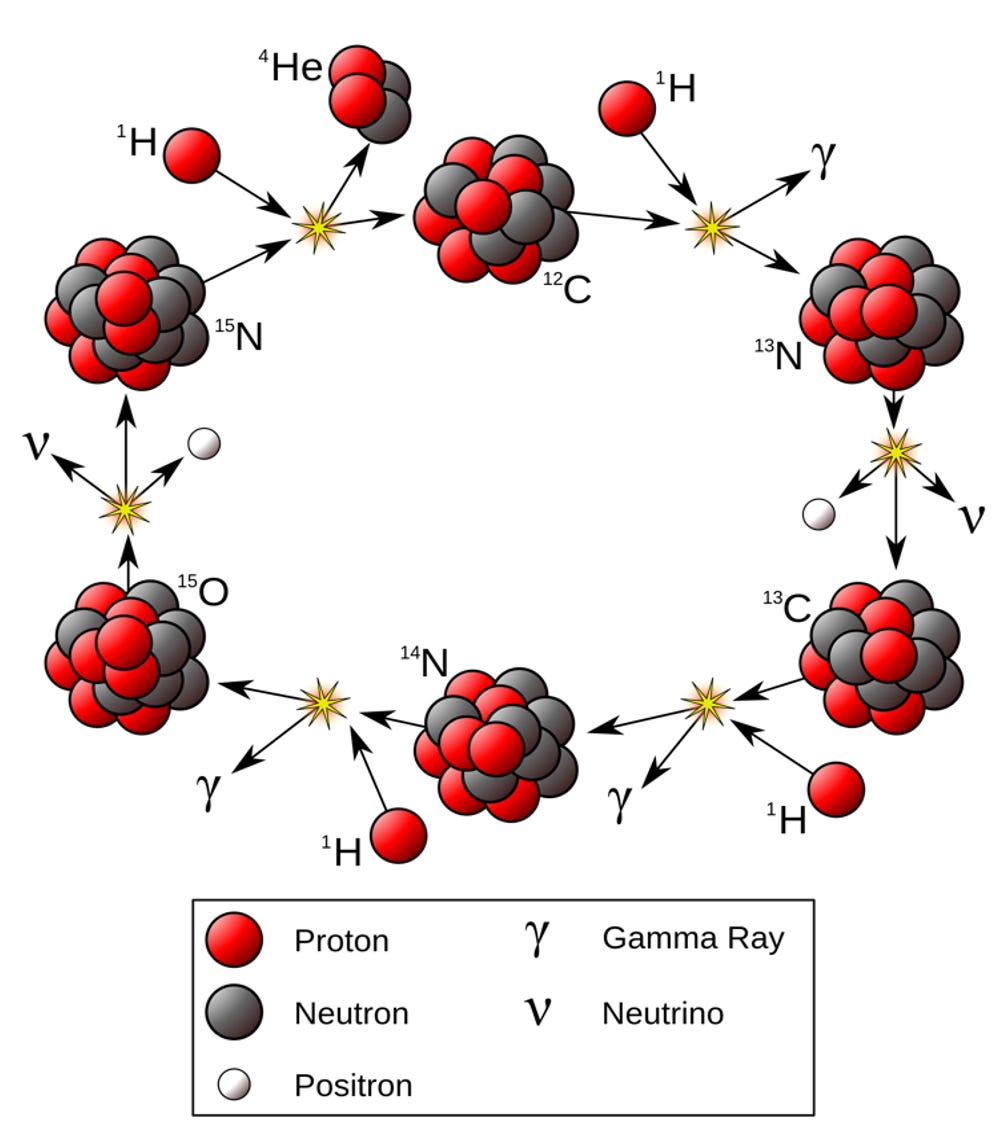

Ongoing nuclear fusion increases the temperature at the core of a star as it emits immense energy in the form of heat and light. When the core increases to a temperature of around 14-15 million Kelvin (human body is around 310 Kelvin), multiple Helium atoms undergo fusion and create Carbon (C), which subsequently creates Nitrogen (N) and Oxygen (O) by fusing with Hydrogen (Helium is also one of the by products) in what is known as the CNO cycle (Figure 2).

Simply put, fusion of lighter elements emits immense energy, increasing the temperature of the star, which creates a suitable environment to fuse heavier elements (need hotter temperatures (more kinetic energy) to overcome the electrostatic repulsion of combining the positively charged nuclei of elements).

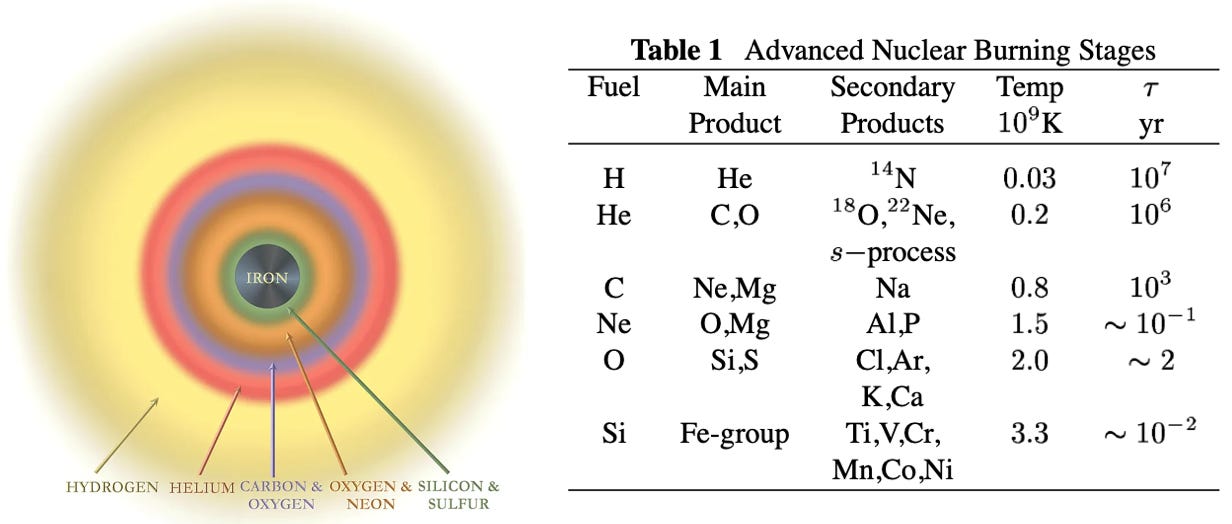

Beyond the CNO cycle, based on the size of the stars (bigger stars can make heavier elements), further nucleosynthesis occurs through fusion of Carbon, Neon (Ne) and heavier elements, and it continues until Iron (Fe) is formed in the core of the star, which does not emit energy, but needs energy to undergo fusion. When a large star (more than 8 times the mass of the Sun) can no longer undergo fusion, its structure is similar to that of an onion, where it has the heaviest element (Iron) in the center and layers of lighter elements all the way up until Hydrogen at its surface (Figure 3). At this stage, due to intense gravity, the core implodes and the outer layers of the star are ejected into space in a colossal supernova explosion.

The supernova hurls out most of the elements that were created in the star into the outer space in enormously huge quantities at extremely high speeds. Here are some observations by NASA’s Chandra X-ray observatory of the Cassiopeia A (Cas A) supernova remnant located about 11,000 light years from Earth.

Cas A has dispersed about 10,000 Earth masses worth of sulfur alone, and about 20,000 Earth masses of silicon. The iron in Cas A has the mass of about 70,000 times that of the Earth, and astronomers detect a whopping one million Earth masses worth of oxygen being ejected into space from Cas A, equivalent to about three times the mass of the Sun.

To understand the scale, the mass of our Earth is 5.972 × 1024 kg (nearly 6 followed by 24 zeros), and that of our Sun is 1.989 x 1030 kg. Now, that amount of matter from the quote is expelled from just one exploding star! When these elements are emitted out in the supernova, they tend to create elements heavier than Iron, until maybe Zirconium (Zr) or Niobium (Nb) through a process called neutron capture (nuclei of elements tend to capture neutrons into them under high speeds and suitable conditions to form heavier elements).

As the outer elements are ejected into space during a supernova, the collapsed core turns into a neutron star (around 20 kilometers in width and weighing as much as our Sun). And when neutron stars in a binary system (two stars revolving around each other) lose their orbital energy, they collide into another one. And this collision of tiny giants, is the primary source of the heaviest stable elements in the universe (Figure 4).

Cosmic dust, planetesimals and planets

A supernova explosion is extremely hot and the ejected material, which is initially in a gaseous state, cools down and condenses into solid with time as it drifts away. The atoms of heavier elements stick together as they cool down and form cosmic dust (10 nanometers – 100 micrometers in diameter) that floats around space. Silicates (compounds of Silicon and Oxygen), and carbon are some components of the cosmic dust. This dust, being very cold and sticky, has the tendency to attract other elements floating around. When a bunch of elements come together on this dust, cosmic rays act as catalysts to break and create bonds between different elements to form compounds like water, methane, carbon monoxide, etc.

Vast amounts of cosmic dust, comprising a wide range of elements and compounds that just keep floating around in space without a care in the world, get dragged into the gravitational field of a newly born star and suddenly start revolving around it in extreme speeds. As they keep revolving, they bump into each other and coalesce (two or more entities merging to become one) into larger bodies called planetesimals (~1 km – hundreds of km in diameter), which, in turn, collide and merge to form planets (thousands to hundreds of thousands km in diameter).

As we reach the end of the first post, take a moment to cherish the fact that almost everything inside and around us that is made up of elements other than the primordial Hydrogen, Helium and traces of Lithium from the Big Bang, was created inside of or as a result of stars in processes spanning billions of years! And yes, almost all the Hydrogen present in the water of all our bodies is the same one from nearly 13.8 billion years ago.

In the next post, let us zoom into a more lively part of our vast universe, something that is near and dear to us.

How was today’s post?

If you liked it, please hit the Like button at the bottom and share it with a friend. Also, please Subscribe to AlterEarth if you haven’t already. Have a great day!

Here are the references that I used for figures and guidance while writing this piece.

References:

https://www.themarginalian.org/2012/11/15/the-birth-of-sound/

https://science.nasa.gov/universe/overview/

https://scienceready.com.au/pages/energy-source-of-stars?srsltid=AfmBOoqCPyanxhBDPj1bU5U5QbbamBoWaYm-udmX4Vqo4yoAQEeiKAgM

https://mcdonaldinstitute.ca/astroparticle-physics-news/borexino-cno-neutrinos/

https://arxiv.org/abs/1406.3462

https://science.nasa.gov/universe/stars/types/#:~:text=Main%20sequence%20stars%20make%20up,millions%20to%20billions%20of%20years.

https://ned.ipac.caltech.edu/level5/Sept16/Rauscher/Rauscher4.html

https://chandra.harvard.edu/elements/

https://chandra.harvard.edu/chemistry/

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/00223131.2002.10875153

https://www.sun.org/encyclopedia/supernova#:~:text=Core%20collapse%20happens%20when%20at,they%20have%20a%20companion%20star.

https://imagine.gsfc.nasa.gov/science/objects/neutron_stars1.html

https://cassaca.org/en/uncategorized-en/2024/02/researchers-discover-cosmic-dust-storms-from-a-type-ia-supernova/